Knowledge Base

In this section, we aim to give you a comprehensive introduction to the fundamentals of light microscopy to help make your microscopy journey more engaging and successful. For each core concept, we’ll provide a brief summary and guide you to reliable resources for more in-depth information.

If you notice something we've missed or have come across an excellent resource related to the techniques discussed, we’d love to hear from you!

If you're still unsure which microscopy technique is best suited for your needs, we recommend watching this lecture by Prof. Ron Vale. In it, he summarizes the key techniques also featured on our website and explains when specific microscopy methods may be most beneficial for different samples or biological experiments.

The most fundamental, but often forgotten step towards a successful microscopy session is the proper alignment of your microscope. In order to achieve optimum system performance and acquire consistent, interpretable image data the illumination of the specimen must be adjusted to the most optimal, even level.

How to set up a microscope for Köhler Illumination should be an ingrained knowledge for every microscope user and should always be the first step of action once you've switched on your microscope.

Practical Advice

"How to set Köhler illumination" (by Humberto Ibarra Avila)

In this pdf you will find a step by step guide to properly set up your microscope for Köhler illumination and thus achieve optimal imaging results:

In this 12min video, Ron Vale talks you through a step-by-step procedure of aligning the lamp and condenser to achieve Koehler illumination.

August Köhler, who first introduced the Köhler illumination procedure, was part of the Carl Zeiss corporation. Here you can read how Zeiss Microscopy explains Köhler illumination.

The educational “MicroscopyU” website of Nikon Instruments explains Köhler illumination with the help of a nice, interactive Java tutorial.

In Darkfield microscopy oblique illumination (i.e. the zero order light is blocked out) is used to create contrast in unstained samples. It is one of the most simple contrasting techniques, with usually quite impressive results.

Here you find a detailed explanation of how darkfield illumination works.

In this half-hour video Prof. Edward Salmon describes the principles of dark field and phase contrast microscopy, two ways of generating contrast in a specimen which may be hard to see by bright field.

Phase contrast is another contrasting method for unstained samples and makes use of the fact that different structures in the sample phase shift the light passing through by different distances. These phase shifts are than made visible by being converted into different levels of brightness in the final image.

Phase contrast is especially suitable for thin samples.

This page contains a comprehensive overview of the technical and historical details of phase contrast microscopy. It also leads you to interactive java tutorials illustrating configurations and alignment.

Here you will find an illustrated step-by-step manual about how to align your micrscope for phase contrast imaging.

In this half-hour video describes how the phase rings work to generate interference between the diffracted and undiffracted light.

The use of two crossed polarizers gives bright contrast to birefrigent objects such as anisotropic crystals and biological polymers.

On this webpage you will find a detailed explanation on how polarization of light works, how we can use the birefrigency of objects to our advantage and learn main applications of polarized light.

Here you will find an introduction to optical birefrigency, which is the prerequisite property for any specimen imaged using polarization microscopy.

In this half-hour video Prof. Edward Salmon describes the components of a polarization microscope (e.g. polarizer, analyzer), birefringence and how it is exploited to generate images, adjusting a polarization microscope, examples of images, and new methods such the LC-Polscope.

Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) is another illumination technique to enhance contrast in unstained, transparent samples.

Orthogonally polarized light is split into two coherent beams, which pass the sample in a parallelized, but sheared (spatially separated) manner. Different features in the sample (thickness, slope, refractive index) then alter the path of both beams to varying degrees, so that when combined again after the specimen, they interfere with each other. Due to the sample-altered path lengths of the light beams, the resulting image has the appearance of a 3D representation.

This page contains a comprehensive overview of the technical and historical details of DIC microscopy. It also leads you to interactive java tutorials illustrating configurations and alignment.

Here you can find step-by-step instructions on how to prepare and align your microscope for DIC microscopy.

In this video Prof. Edward Salmon discusses the mechanism of the DIC (Wollaston) prisms along with how to generate optimal contrast.

In todays life sciences, only few microscopic samples and experiments can be satisfyingly imaged using stain-free contrasting methods such as described previously. Most users that come to our facilities want to image fluorescently labeled samples.

Fluorescent substances (fluorochromes) absorb light of a specific wavelengths range and (usually) emit longer wavelengths light (Stokes' shift). A fluorescent microscope uses different filters to distinguish between excitation and emission light. The emission light is then captured by the detector (eg. camera). Using multiple fluorochromes, different structures of one microscopic specimen can be labeled, imaged and analyzed simultaneously.

On these two pages you will find very detailed introductions to the basic concepts of fluorescence and fluorescence microscopy: fluorescence intro 1, fluorescence intro 2

On this page fluorescence microscopy is discussed in various chapters featuring all aspects of a fluorescence microscope.

This webpage as well gives you an introduction to fluorescence microscopy, but also features on the importance of various light sources and objectives to your imaging result.

In this video Nico Stuurman describes the principles of fluorescence and fluorescence microscopy.

There are two common ways of getting your sample to fluoresce:

Fluorescent proteins

You can make a transgenic line of your model organism that stably expresses a certain fluorescent protein (e.g. GFP ... green fluorescent protein). If there is no established line which targets your feature of interest, than making one can cost you a lot of time and resources. Once a line is established, it is a great tool and you always have a fluorescent sample available without the need for extensive staining protocols. However, you might also want to consider that this method makes you less flexible to react to changes on your (the facilities') fluorescent microscope (eg. changes of filters, light sources).

Here you find a comprehensive list of available fluorescent proteins combined with a great interactive graph. You may filter the plot and compare by excitation and emission wavelength, Quantum yield, brightness, stability and and and.

If you are interested in the history of fluorescent proteins, have a look here.

And here another, well structured overview of fluorescent proteins.

Fluorescent dyes

Fluorescent dyes are fluorochromes which you target to your structure of interest via antibodies. For this, extensive staining protocols are necessary, the outcome of which can vary widely regarding specificity, brightness and stability. While this might be seen as a limitation, antibody fluorescent stainings offer huge flexibility. With an elaborate amount of different first and second antibodies on offer the whole system can be easily adapted to various external factors.

In the following we provide links to comprehensive databases of both fluorescence proteins and dyes with sorted spectras and including lasers, lamps and filter sets.

- ThermoFisher Fluorescence Spectra Viewer

- BD Biosciences Spectrum Viewer

In most fluorescent microscopes filters are needed to distinguish between excitation and emission light, to narrow down the wavelength band passing through or to split between several parallel excitation or emission wavelengths.

Chroma Technology Corp is one of the leading international manufacturers for optical filters.

In their “Handbook of Optical Filters for Fluorescence Microscopy” you will find an introduction to fluorescence microscopy as well as discussions about optical filters in general and fluorescence filters in specific.

Semrock is another leading international manufacturers for optical filters, giving a nice introduction to optical filters on their webpage.

Here, AHF Analysentechnik explains their Filtersystems.

Read here how best to combine fluorescence filters.

One of the big aims in microscopy is to achieve optical sectioning in order to bring features of interest into focus or, in other words, to achieve confocality.

To reach this goal, many different methods have been developed in the past decades. Some of them adapt specific hardware, others achieve confocality post-aquisition through highly specialized software. And some again combine both ways.

Here we strive to give a comprehensive overview of what techniques there are available in the field of light microscopy.

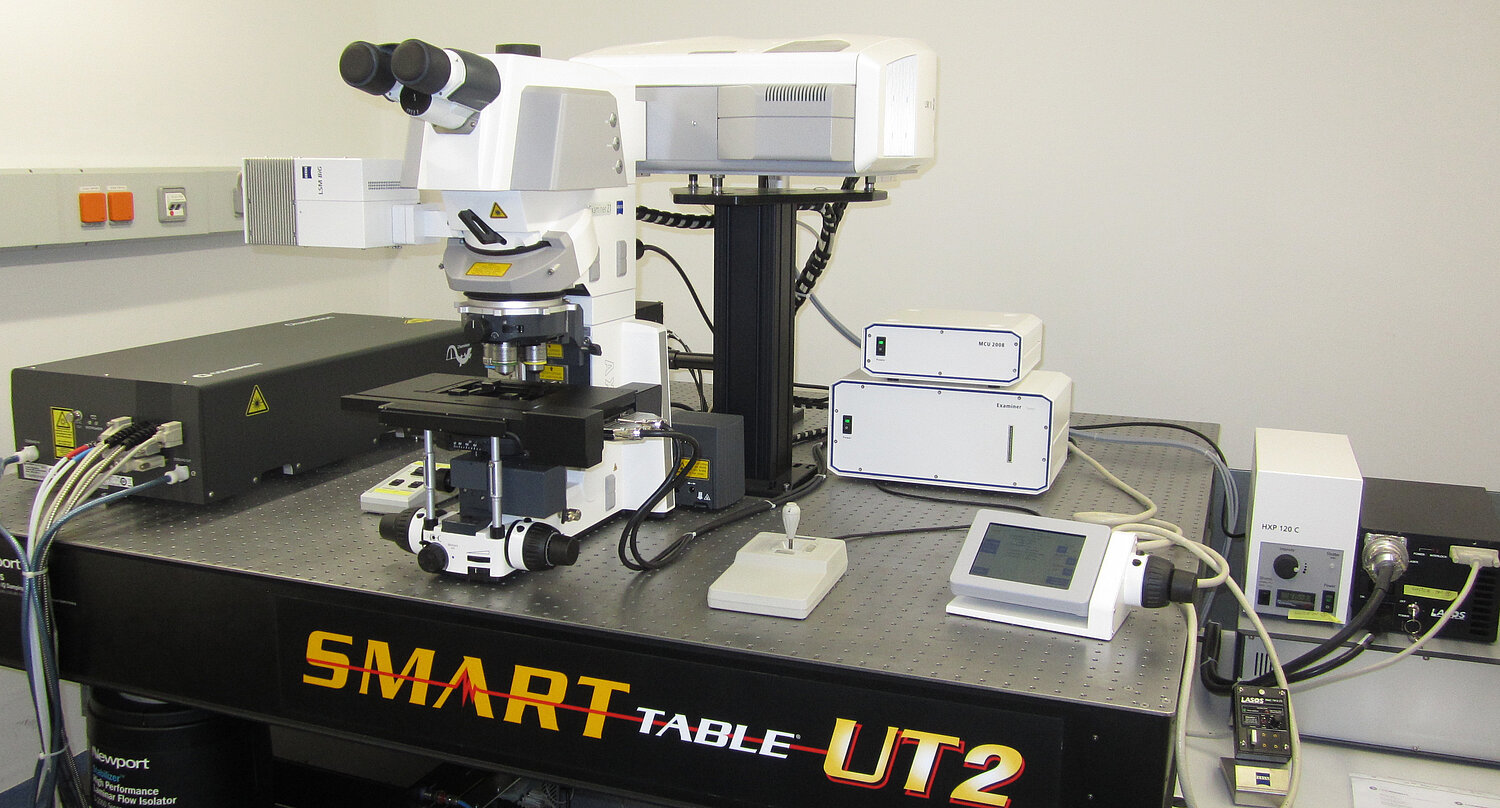

In a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) a focused laser beam is scanned over your sample, such that the image is acquired point by point. Before each point is collected and amplified by the detector (commonly a Photo Multiplier Tube - PMT), the emission light has to go through a spatial, adjustable pinhole which effectively cuts off the out of focus light.

There is NO CAMERA on your confocal!

Or: the virtues of a cameraless microscope system. What is a PhotoMultiplier Tube (PMT) and how does it work: have a look.

Very cool Java tutorial on how a confocal microscope system works and which adjustable parameters lead to what results, including a comprehensive explanation.

Here you find an introduction to the principles and the history of confocal microscopy.

Read, how to optimally prepare your sample so as to get most out of your confocal microscope.

In this 26min video Dr. Thorn discusses the basic principles of confocal microscopy, with specific discussions of the operation of laser scanning and spinning disk confocal microscopes and of their application to biology.

Multiphoton microscopy is another scanning point illumination technique, where a pulsed IR laser is used to achieve a much higher penetration depth than with "conventional" lasers and is therefore very well suited for very thick and/or optically dense samples. Due to the 2-photon effect, your fluorophore is only excited at the focal plane, thus reducing photo toxicity and light scattering.

The lower z-resolution due to the higher excitation wavelength is one of the drawbacks, also multicolour imaging proves more challenging.

On this webpage you can find a detailed introduction to multiphoton microscopy, including some interactive java tutorials.

Here you find an explanation about the fundamentals and applications in multiphoton excitation microscopy

This half an hour talk by Kurt Thorn introduces two-photon microscopy which uses intense pulsed lasers to image deep into biological samples.

A fast rotating, synchronized pinhole disc in combination with virtual "field" illumination and camera detection enables confocal imaging at a much higher temporal resolution than conventional Laser Scanning Confocal. Using Spinning Discs, even confocal live cell imaging of moving objects is possible.

Drawbacks are a lower z-resolution and compromises on the confocality for lower magnification/NA objectives.

Here you can find a detailed introduction to spinning disc microscopy, including the history and a comparison to conventional confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Here, Zeiss Campus explaines the fundamentals of a spinning disc by using a nice interactive tutorial.

This 25min talk by Kurt Thorn introduces confocal microscopy, and discusses optical sectioning, reconstruction of 3D images, and how the laser-scanning confocal microscope and spinning disk confocal microscope work.

By using high angle incident light, an evanescent wave is created in Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, which only excites fluorophores in a thin (~200nm) zone very near a solid surface (eg. a cell membrane sitting on a coverslip).

The resulting image displays very low background noise and virtually no out-of-focus fluorescence.

Here you can find a detailed introduction to the theoretical aspects of TIRF microscopy, including a interactive Java tutorial in which you can explore the TIRFM evanescent wave.

This webpage shows another, nicely illustrated, detailed introduction to TIRF microscopy.

In this 43min. video, the pioneer of TIRF Microscopy (Prof.em. Daniel Axelrod) describes what this technique is used for, explains the principles of the evanescent wave, gives many examples of different microscope configurations used in TIRF, and shows how polarized light TIRF can be used to image membrane orientation.

Light sheet microscopy, better known as single plane illumination microscopy (SPIM) is an emerging technique that combines optical sectioning with multiple-view imaging. The optical sectioning is achieved by using a thin light sheet to illuminate the sample perpendicular to the optical axis, the entire field of view being acquired by a camera.

There are various approaches to mount your (big) sample, many of which aim to assure a free rotation of the object. This way, multiple views of the same sample can be imaged and combined through a processing algorithm (eg Fiji Multiview Reconstruction) to create a 3D representation.

Due to the mainly non-invasive mounting techniques live-organism imaging is not only possible, but one of the main targets.

In this half an hour talk Dr. Ernst Stelzer discusses the new technique of light sheet microscopy, also known as selective plane illumination (SPIM):

Here you can find a reference library on top publications about light sheet microscopy.

Open SPIM

OpenSPIM is an Open Access platform for building, adapting and enhancing SPIM technology. It is designed to be as accessible as possible, which includes:

- detailed, easy-to-follow build instructions

- off-the-shelf components and 3D-printed parts

- modular and extensible design

- completely Open blueprints

- completely Open Source

Structured illumination combines hardware and software techniques to achieve optical sectioning. A hardware grid pattern (ie. a pattern of dark and light stripes) is focused onto the sample and shifted several times, one image being acquired by camera after each shift. A subtractive software algorithm is then used to reconstruct the in-focus-image.

ApoTome

The Zeiss ApoTome is one example of the implementation of structured illumination to achieve optical sectioning of thick, fluorescently labeled specimen.

Here, Zeiss explains its structured illumination system with the help of an interactive Java tutorial.

Deconvolution is a software based method to achieve optical sectioning. It corrects the systematic error caused by the objective lens in that smaller and smaller object features come through the lens with less and less contrast than they have in reality. This is true for all widefield, confocal, 2 photon, SPIM/LSFM etc modes of fluorescence light microscopy.

Once corrected by deconvolution, the resulting image is a more quantitative estimate of the true distribution of fluorophores in the object, with increased contrast and dynamic range especially for smaller features. Also, photon and detector noises, as well as background and detector offset are suppressed and the image appears "deblurred" (ie. sharper) to the eye.

In this lecture, Prof. David Agard describes the basic principles of various deconvolution techniques and introduces principles important to deconvolution such as the Fourier transform, points spread function and optical transfer function.

Here, you can find a nice theoretical introduction into how deconvolution in optical microscopy works.

This is a very nice, basic (not too mathematical) explanation of deconvolution.

SVI is the developer and distributer of a professional deconvolution software: Huygens. On their webpage they give nice tutorial videos on how deconvolution (in general and with Huygens in specific) works, including some nice examples.

Refractive Index Calculator

For deconvolution a proper spherical aberration correction is crucial. Here, you can calculate the correct refractive Index for your immersion oil.

coming soon …

coming soon …

In 1873 Ernst Abbe defined the so-called "diffraction barrier": the spatial resolution limit attainable with conventional light microscopy as follows. Resolution is the light wavelength divided by twice the numerical aperture of the lens. A reasonable approximation to that is the full width half maximum (FWHM) of the point spread function of an optical system; the image of a point source of light. For example, a widefield microscope with a high numerical aperture (NA) objective (eg. 1.4), using a wavelength within the visible spectrum (eg. 550 nm), would give a resolution of about 200 nm.

However, in recent years different light microscopy techniques have been developed to work around this limit and to image and resolve features smaller than the diffraction barrier.

Here you can find more about the history and technical concepts of superresolution.

In this lecture, Prof. Xiaowei Zhuang surveys a variety of recent methods that achieve higher resolution than is possible with conventional microscopy with diffraction-limited optics. These include different types of patterned illumination (e.g. STED and SIM microscopy) or techniques that build up an image by stochastically switching on single fluorescent molecules and localizing each molecule with high spatial precision (STORM, PALM, FPALM).

In the following, we aim to give you a brief overview of the super resolution techniques accessible to you on the campus and lead you to further interesting readings about them.

Reviews about supper resolution techniques:

- Schermelleh et. al. 2010, JCB, A guide to super-resolution fluorescence microscopy

- Heintzmann et. al., 2017, Chem. Review, Super-Resolution Structured Illumination Microscopy

- Schermelleh et. al., 2019, Nature Cell Biology, Super-resolution microscopy demystified

One of the best known superresolution techniques is STimulated Emission Depletion (STED) microscopy. Besides the normal, exciting laser beam this techniques uses a second, doughnut shaped beam around the focus point with which to selectively deplete fluorphores. With this approach the actual excited area is minimized, thus increasing the achieved resolution beyond the diffraction barrier.

As a result of the development of this technique, Stefan Hell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2014.

Here, Stefan Hell, who invented many of the methods allowing a resolution beyond the diffraction barrier, gives an introduction to these super-resolution microscopy techniques, and a detailed discussion of two such techniques: STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion) and RESOLFT (REversible Saturable OpticaL Fluorescence Transitions).

Find here an introduction to the STED concept. Includes an interactive Java Tutorial.

This tutorial explains the principles of STED super-resolution microscopy - from the underlying photo physical processes to the integration into a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Picoquant explains STED and introduces their implementation of it.

Find out more about the fundamentals of STED.

Here you can find a very detailed explanation of the principles of PALM and its possible applications.

In this lecture Prof. Xiaowei Zhuang begins by explaining that the resolution of traditional light microscopy is about 200 nm due to the diffraction of light. This diffraction limit has long hampered the ability of scientists to visualize individual proteins and sub-cellular structures. The recent development of sub-diffraction limit, or super resolution, microscopy techniques, such as STORM, allows scientists to obtain beautiful images of individual labeled proteins in live cells. In Part 2 of her talk, Zhuang gives two examples of how her lab has used STORM; first to study the chromosome organization of E. coli and second, to determine the molecular architecture of a synapse:

Find here a basic description to the PALM concept. Includes an interactive Java Tutorial.

During their 20-years friendship, nobel prize winning Eric Betzig and Hess worked together and separately, in academia and industry, before eventually joining forces to develop the first super-high-resolution PALM microscope. They tell us the story of this journey and emphasize how their unusual and varied backgrounds provided the skills to complete the project: Betzig and Hess

Find here another basic description to the PALM concept. Includes an interactive Java Tutorial.

In confocal-like structured illumination systems such as Apotome, Optigrid, DSD, and indeed point scanning and spinning disk confocal systems, structured illumination is primarily used to increase image contrast. Further benefits of even higher contrast and doubled resolution are possible using a 3D structured illumination pattern of light projected into the sample.

This 3D structured illumination results in the formation of Moiré patterns: Interference fringes between the light pattern and the sample fluorescence distribution. Multiple images are required such that the light covers all the sample over the image series. The diffraction limited patterns contain doubled resolution information that can be retrieved by the mathematical trick of Heterodyning, a very common method in engineering and signal processing. The processing consist of two parts: extracting the higher resolution information from the interference fringes, and applying a deconvolution based on the system's PSF, and results in a reconstructed image with very high contrast (particularly in the usually poor axial, z direction) and doubled resolution in all axes.

3D-SIM out-performs point scanning confocal in speed, sensitivity, contrast and resolution for samples where the 3D light pattern is not disturbed by the sample, such as bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cell monolayers and even thick sections when mounted in high refractive index media.

Sample preparation tips

- All Fluorophores can be used for 3D SIM, but it is recommended to match the lasers available on the systems

- Use high precision #1.5 coverslips

- Use mounting media without DAPI such as Vectashield or Prolong Diamond

- Use samples with high labelling density and low background

- Optimize the fixation (e.g. y adding a small percentage of glutaraldehyde, fixation at 37°C)

- Reduce the refractive index mismatch by choosing correct immersion oil (OMX)

OMX

OMX stands for Optical Microscope eXperimental, and came out of the Sedat lab in California, with hardware and image reconstruction software licenses to Applied Precision for the DeltaVision range of microscopes, then bought by GE Healthcare.

The traditional microscope stand, built around a human's eyes and hands was discarded, and instead the microscope was redesigned around having multiple cameras and a fixed inverted objective lens and nano motion xyz sample stage. This was to optimise the OMX for modern high performance biological fluorescence microscopy: Simultaneous multicolour widefield imaging with deconvolution and specifically, very high performance 3D-SIM.

Ring TIRF is also available on the OMX as a module. OMX has a second generation patterned light engine called Blaze. This makes live cell imaging with 3D-SIM possible, compared to the first generation slow, unstable mechanical pattern generators.

Structured Illumination TIRF Microscopy (2D-TIRF-SIM)

Combining TIRF with 2D-SIM both increases contrast, and can double spatial resolution.

Online tutorials

SIM original publication

- Gustafsson et. al., 2001, Journal of Microscopy Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy

- Gustafsson et. al., 2008, Biophys. J. Three-Dimensional Resolution Doubling in Wide-Field Fluorescence Microscopy by Structured Illumination

Reviews

- Heintzmann et. al., 2017, Chem. Review, Super-Resolution Structured Illumination Microscopy

- Wu et. al., 2018, Nature Methods, Faster, sharper and deeper: structured illumination microscopy for biological imaging

Sample preparation

- Demmerle et. al., 2017, Nature Protocols, Strategic and practical guidelines for successful structured illumination microscopy

- Kraus et. al., 2017, Nature Protocols, Quantitative 3D structured Illumination microscopy of nuclear structures

- Pereira et. al, 2018, Biorxiv, Fix your membrane receptor imaging: actin cytoskeleton and CD4 membrane organisation disruption by chemical fixation

- Huebinger et. al. 2018, Scientific reports, Quantification of protein mobility and associated reshuffling of cytoplasm during chemical ficxation

Software/plugins

- FAIRsim: SIM reconstruction open-source plugin for ImageJ, Müller et al., 2016

- SIMcheck: SIM data quality assessment in ImageJ, Ball et. al., 2015

- NanoJ-Squirrel: Check for optical imaging artifacts, Culley et al., 2018

- Chromagnon: Chromatic aberration correction, Matsuda et al., 2018

Measurements were carried out and plots generated at MPI-CBG LMF, using the J457 Automatic Refractometer (RUDOPLH) for each medium, in a temperature range between 10 and 60 Celsius degrees at 1 degree steps.

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

© MPI-CBG LMF

Resolution is considered one of the most important parameters in light microscopy, as the resolving power of your microscope determines the size of the smallest feature within your sample that is optically still detectable. When explaining resolution, the term PIXEL is almost unavoidable. PIXEL is an abbreviation for "picture element" and defines how many single points (elements) your picture consists of.

However, commonly the word PIXEL is used for two different concepts: the elements of your picture on screen, as well as the elements on your camera chip. This can cause no little confusion when trying to explain the concept of resolution to someone who is new to the field of microscopy.

For example:

PIXEL size (???which one?? -> camera chip) / magnification = PIXEL size (???which one?? ->image)

We therefore propose the additional use of the word DEXEL, this being an abbreviation for "detector element" and describing the actual physical elements that make up the camera chip. This would lead to a much more straight forward explanation of resolution for a camera based microscope.

Our previous example would now look like that:

DEXEL size / magnifcation = PIXEL size

Now a PIXEL is ALWAYS a picture element, meaning a point source (please see below "A pixel is not a little square"), whereas the word DEXEL covers the physical elements on the sensor of your camera (which may or may not indeed be little squares).

If you find yourself thinking "but... a pixel is a little square...isn't it!?", please read this paper.

Because, frankly, this line of thinking is simply incorrect!

coming soon …

In this section you can find a collection of companies that sell imaging equipment starting from individual components such as filters, light sources etc. up to entire light microscopy systems. We tried to sort them according to the products they sell and manufacture, respectively. The list is far from being complete and will be constantly updated.

If you know of a company that is not listed here but you think it should be then let us know!

Phasefocus

Phasics

TESCAN

Tomocube